Could a Tiny Fish Hold the Key to Curing Blindness?

NIH, National Eye Institute (NEI) via Newswise – Imagine this: A patient learns that they are losing their sight because an eye disease has damaged crucial cells in their retina. Then, under the care of their doctor, they simply grow some new retinal cells, restoring their vision.

Although science hasn’t yet delivered this happy ending, researchers are working on it – with help from the humble zebrafish. When a zebrafish loses its retinal cells, it grows new ones. This observation has encouraged scientists to try hacking the zebrafish’s innate regenerative capacity to learn how to treat human disease. That is why among the National Eye Institute’s 1,200 active research projects, nearly 80 incorporate zebrafish.

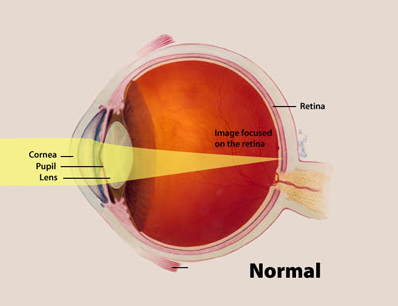

The retina is a layer of tissue in the back of the eye that responds to light. But many scientists think of the retina as part of the brain. Like other neurons of the central nervous system, retinal neurons typically don’t replicate in adult humans. Loss of retinal neurons typically results in irreversible vision loss.

Image credit: National Eye Institute

However, zebrafish, like newts, frogs, and a strange fish-like salamander called the axolotl, can regrow a variety of body parts – not only retinal neurons, but also the heart, fins, pancreas, brain, spinal cord, and kidney.

Zebrafish have a variety of traits that make them a great model for studying tissue regeneration: They’re capable of reproducting hundreds of offspring at a time. They’re cheap to maintain and express about 70% of the same genes that humans do. Unlike mice, which develop in a womb, zebrafish develop externally where scientists can easily observe them. And their flesh is nearly transparent during development, enabling researchers to observe their internal organs.

Scientists have long known that when zebrafish retinas are damaged, neuronal support cells called Müller glia start dividing to create neuronal precursor cells, which go on to become replacement retinal neurons. More recently, scientists have been trying to unravel the biological factors that initiate this process. Progress in that effort is detailed in several NEI-supported research projects over the past three years.

Studying zebrafish, James Patton of Vanderbilt University and colleagues found that when levels of the neurotransmitter GABA decrease, neural stem cells activate. These cells then migrate to damaged retina and develop (differentiate) into whatever cell type is needed for repair. Patton’s findings help identify cues that stimulate zebrafish regeneration.

Jeff Mumm, Johns Hopkins University, reported that immune cells in the retina called microglia are necessary for zebrafish Müller glia to initiate regeneration after injury. After selectively knocking out microglia with a toxic enzyme, Mumm found that the Müller glia showed almost no regenerative activity after three days of recovery, compared with approximately 75 percent regeneration in control zebrafish. However, when an immunosuppressant was applied to inhibit microglia reactivity a day after retinal cell loss had begun, the pace of retinal neuron replacement accelerated. This observation suggests that microglia play different roles at different stages of injury/regeneration.

![]()

Jeff Mumm, Johns Hopkins, and collaborators, fluorescently labeled immune cells in zebrafish larvae to track immune system activity in a model of retinal degeneration. Image credit: Credit: David White, Mumm Lab, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Findings in zebrafish by these other groups led Tom Reh at the University of Washington to unlock the regenerative potential of cells in the mouse retina. In newborn mice, the gene regulatory factor Ascl1 can direct Muller glia to become retinal neurons. This gene goes dormant when mice mature. By artificially expressing the Ascl1 gene in adult mouse Muller glia, Reh’s team turned the gene program back on, showing for the first time that Müller glia in the adult mouse can give rise to new functional neurons after injury. These neurons have the gene expression pattern, the morphology, the electrophysiology, and the epigenetic program to look like interneurons instead of glia, according to the report, and connect with the existing retinal circuitry and respond to light.

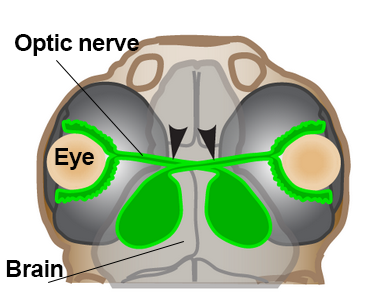

A second major challenge of regenerating the visual system is figuring out how replacement neurons in zebrafish find their way back to visual centers of the brain. The light-sensing photoreceptors connect to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). RGC cell fibers called axons coalesce within the optic nerve where they exit the eye and disperse throughout the brain.

Beth Harvey, a postdoctoral researcher working with Michael Granato at the University of Pennsylvania, has developed a model for studying this process.1 She uses zebrafish at the late larval stage so that she can observe RGC axons navigate to their appropriate brain target after injury, using a technique called confocal microscopy. Interestingly, she found that axons are more likely to innervate appropriate targets when the optic nerve is only partially cut—like leaving a trail of breadcrumbs for regenerating axons to follow.

Illustration of zebrafish head showing optic nerve, eye, and brain. Image courtesy of Beth Harvey, University of Pennsylvania.

To accelerate progress, the NEI funded a consortium of scientists as part of its Audacious Goals Initiative to identify biological factors that affect the restoration of functional connections within the retina and between the eye and brain. Projects within the consortium have used various models to evaluate hundreds of genes for their role in regeneration as well as compounds that modify their activity. In partnership with Michael Dyer from St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital, the NEI is uploading consortium data to an online database to help future investigations.

References

1. Harvey, B. M., Baxter, M. & Granato, M. Optic nerve regeneration in larval zebrafish exhibits spontaneous capacity for retinotopic but not tectum specific axon targeting. PLoS One 14, e0218667, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218667 (2019).

To read the original article click here.