Ginger Powder as a Pain-Killer?

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM via Nutrition Facts – There have been at least eight randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ginger for pain.

You may recall that I’ve previously explored the use of spinach for athletic performance and recovery, attributed to its “anti-inflammatory effects.” Most athletes aren’t using spinach to beat back inflammation, though; they use drugs, typically non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, which is used by up to 95 percent of collegiate athletes and three quarters of kids playing high school football. They aren’t only using it for inflammation, though, but also prophylactically “prior to athletic participation to prevent pain and inflammation before it occurs. However, scientific evidence for this approach is currently lacking, and athletes should be aware of the potential risks in using NSAIDs as a prophylactic agent,” which include gastrointestinal pain and bleeding, kidney damage, and liver damage.

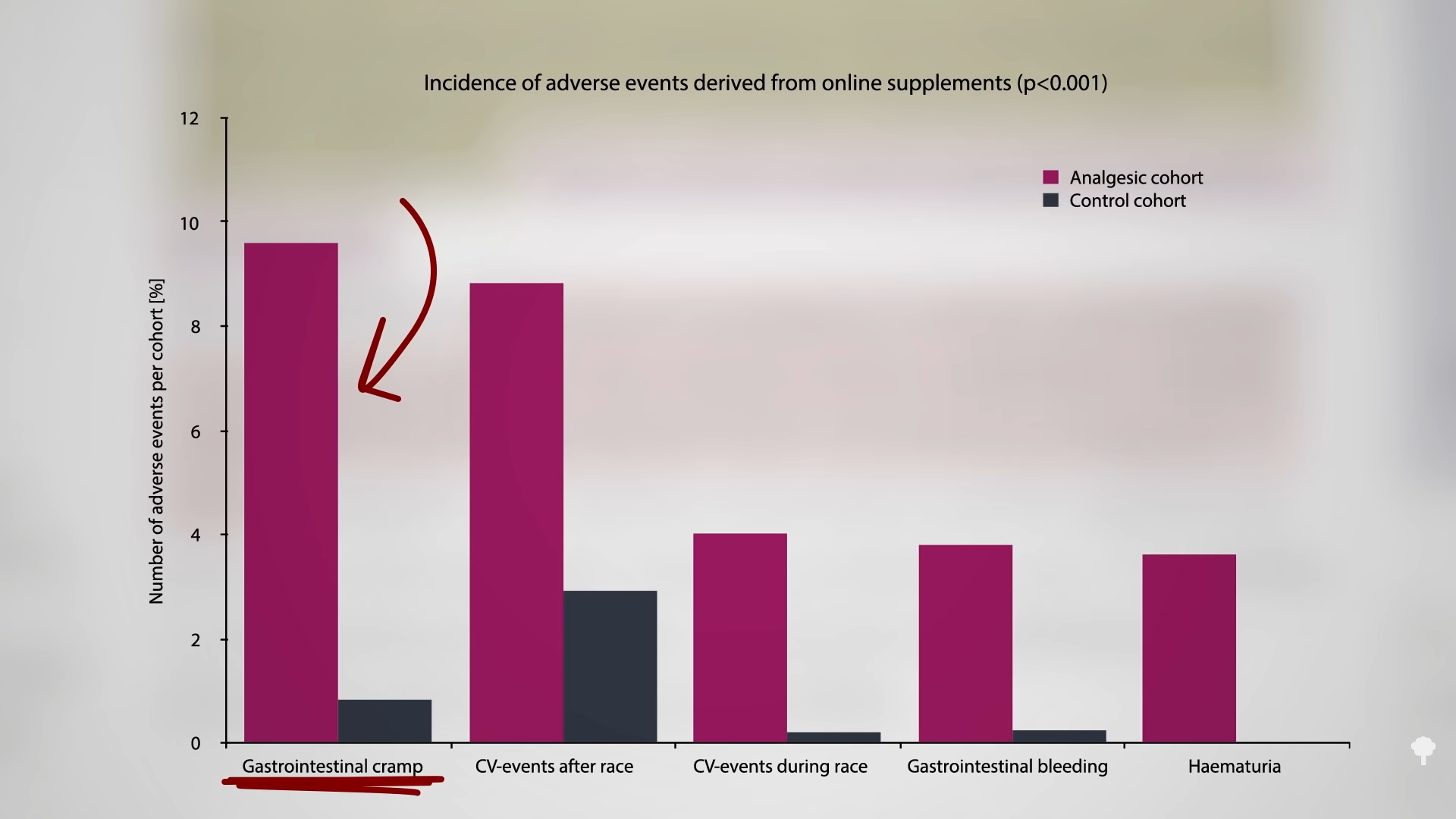

There was one study in particular that freaked everyone out: A study of thousands of marathon runners found that those taking over-the-counter pain killers before the race had five times the incidence of organ damage. Nine were hospitalized—three with kidney failure after taking ibuprofen, four with gastrointestinal bleeding after taking aspirin, and two with heart attacks, also after aspirin ingestion. In contrast, none of the control group ended up in the hospital. No pain killers, no hospital. What’s more, the analgesics didn’t even work. “Analysis of the pain reported by respondents before and after racing showed no major identifiable advantages” to taking the drugs, so it appeared there were just downsides.

What about using ginger instead? That’s the subject of my video Ground Ginger to Reduce Muscle Pain. In that marathon study, as you can see below and at 1:33 in my video, the most common adverse effect of taking the drugs was gastrointestinal cramping. Ginger, in contrast to aspirin or ibuprofen-type drugs, may actually improve gastrointestinal function. For example, endurance athletes can suffer from nausea, and ginger is prized for its anti-nausea properties.

Okay, but does it work for muscle pain?

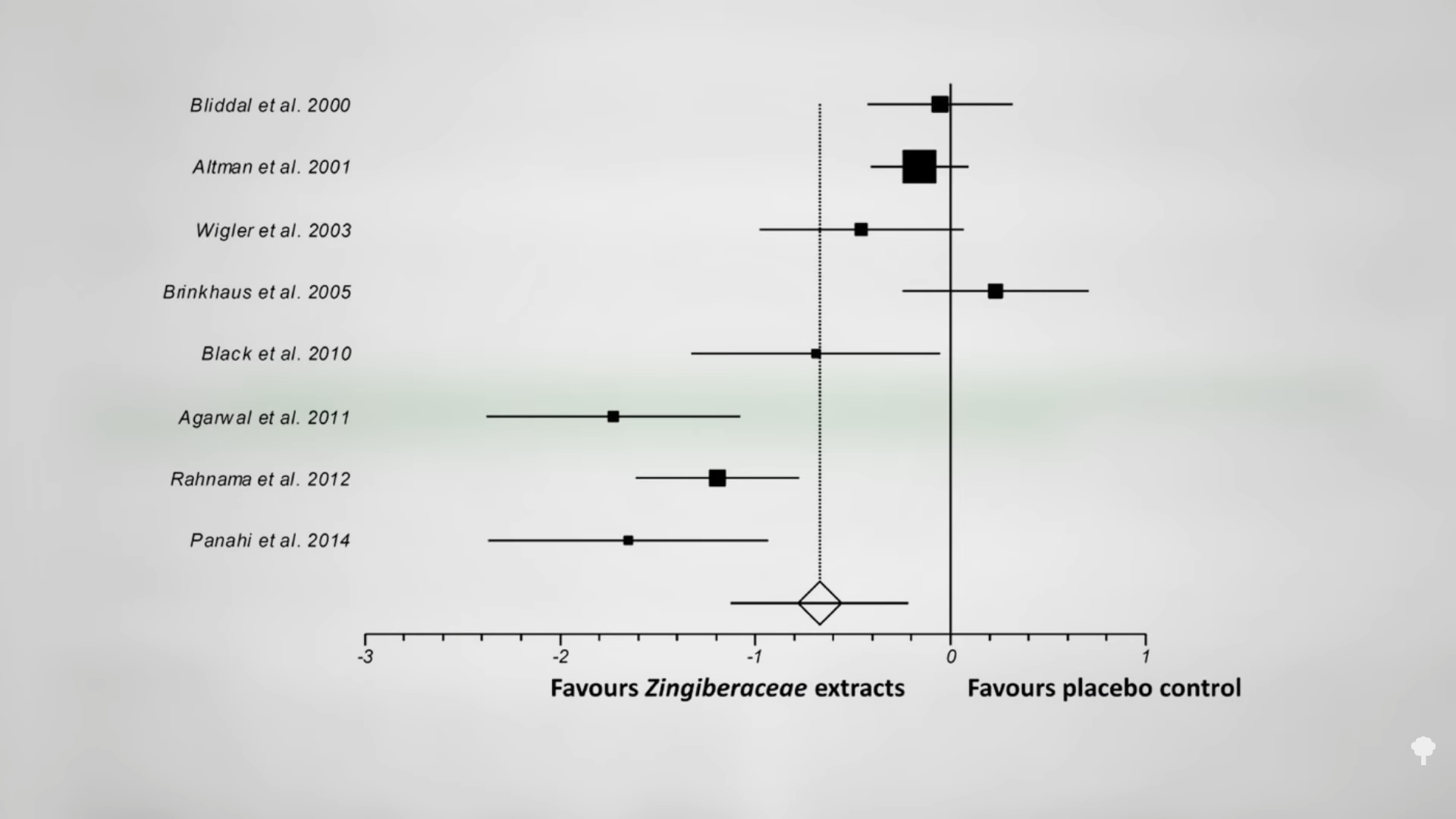

There have been at least eight randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ginger for pain—for everything from osteoarthritis to irritable bowel to painful periods. I’ve made videos about all of those, as well as its use for migraine headaches. Overall, ginger extracts, like the powdered ginger spice you’d get at any grocery store, were found to be “clinically effective” pain-reducing agents with “a better safety profile than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.” As you can see below and at 2:22 in my video, the ginger worked better in some of the studies than in others, which is “likely to be at least partly due to the strong dose-effect relationship that [was] identified and the wide range of doses used among the studies under analysis (60-2000 mg of extract/day).”

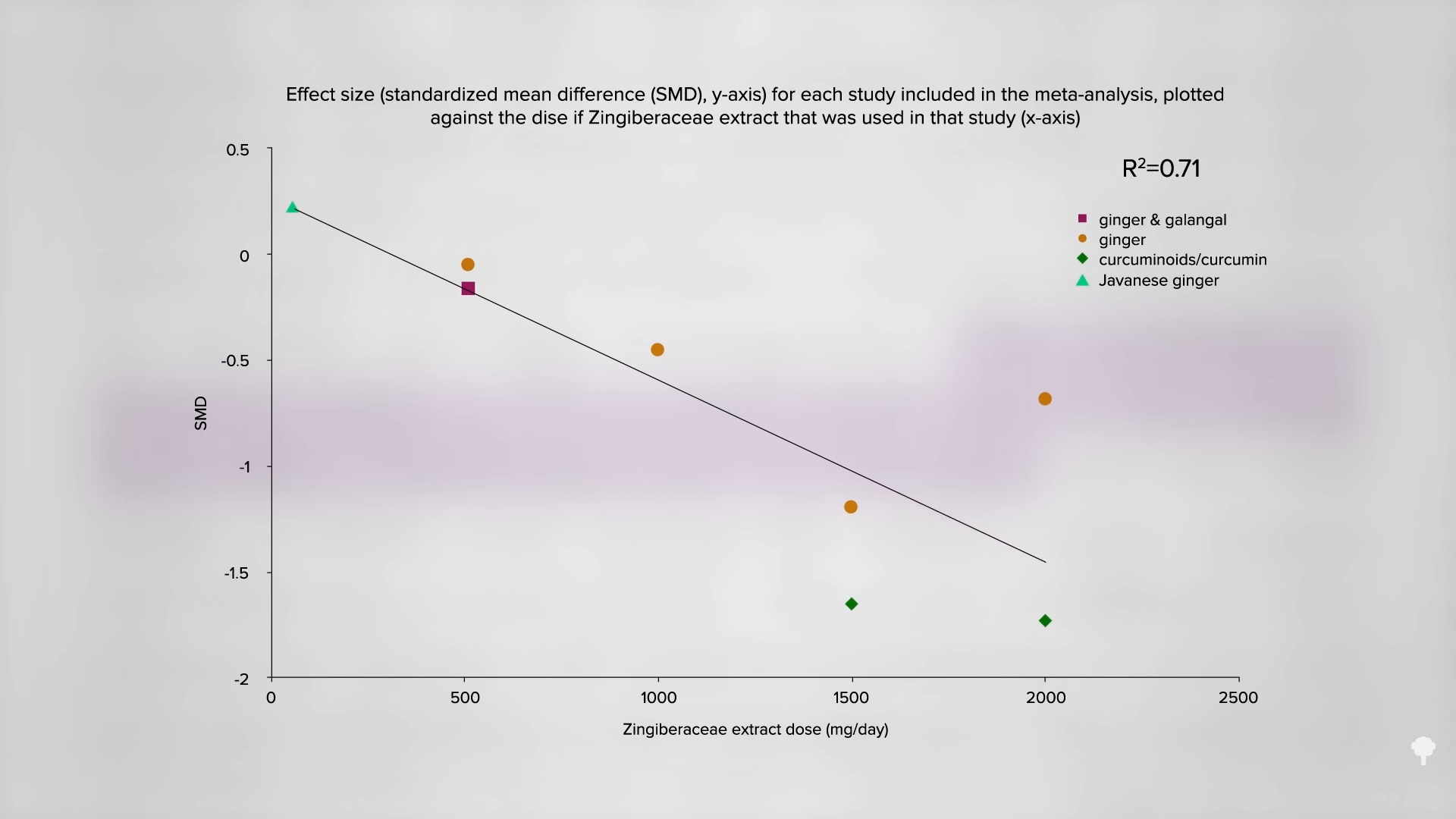

In terms of reduction of pain, as you can see below and at 2:32 in my video, the best results were achieved with one and a half or two grams a day, which is a full teaspoon of ground ginger.

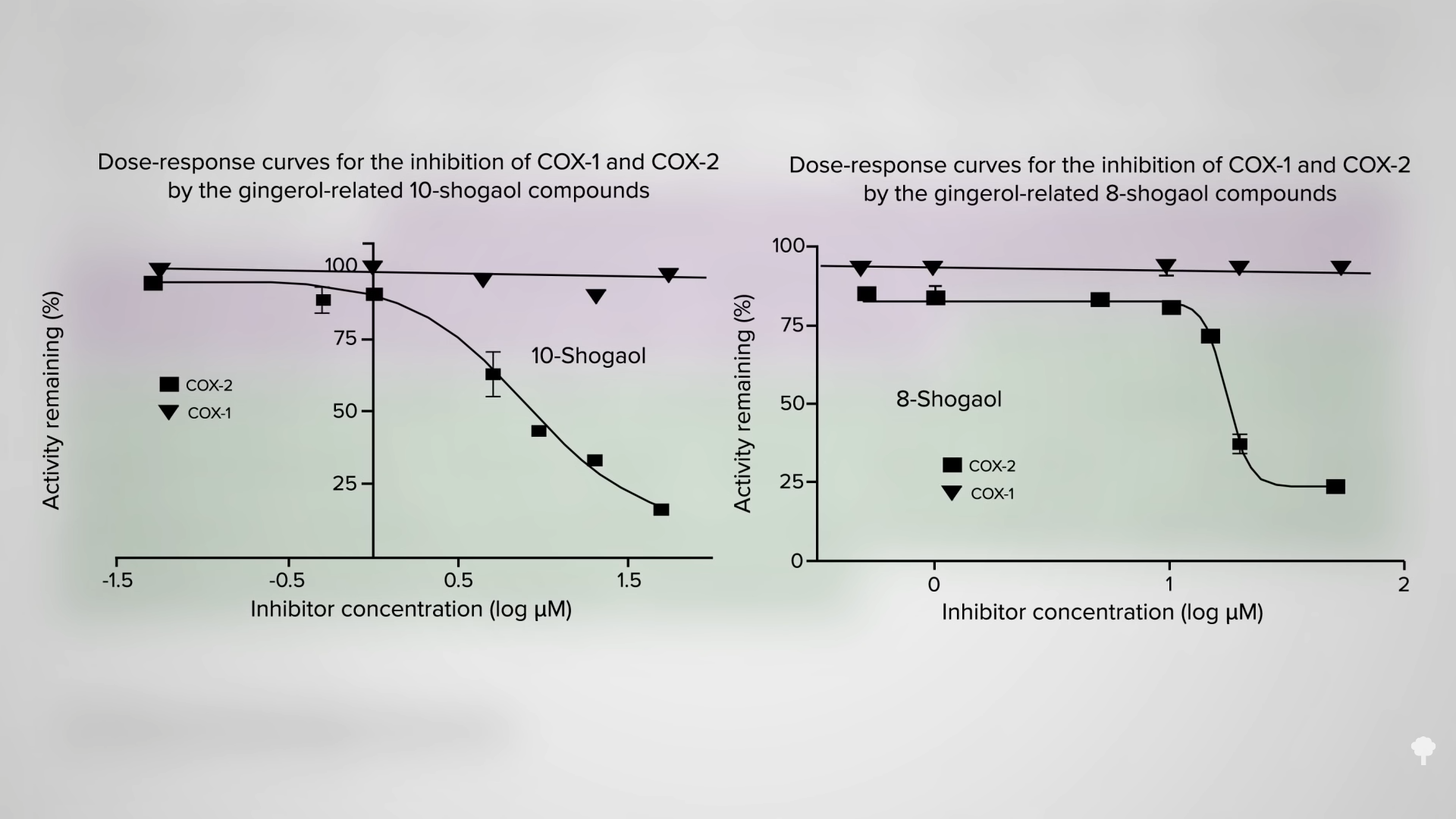

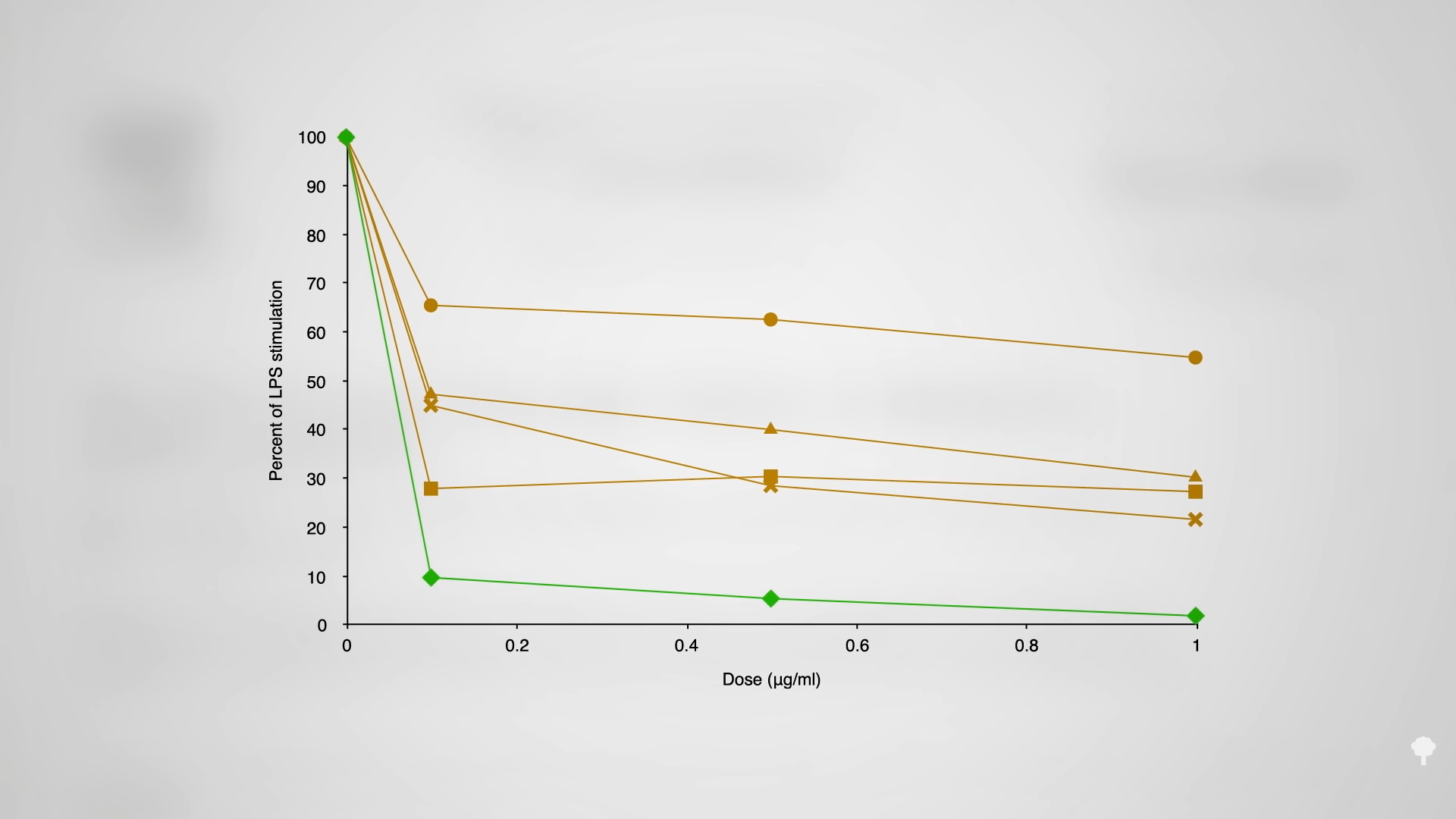

The drugs work by suppressing an enzyme in the body called cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which triggers inflammation. The problem is that they also suppress cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), which does good things like protect the lining of your stomach and intestines. “Since inhibition of COX-1 is associated with gastrointestinal irritation, selective inhibition of COX-2”—the inflammatory enzyme—“should help minimize this side effect” and offer the best of both worlds. And, that’s what ginger seems to do. As you can see below and at 3:11 in my video, two ginger compounds had no effect against COX-1, the “good” enzyme, but could dramatically cut down on COX-2, the pro-inflammatory one.

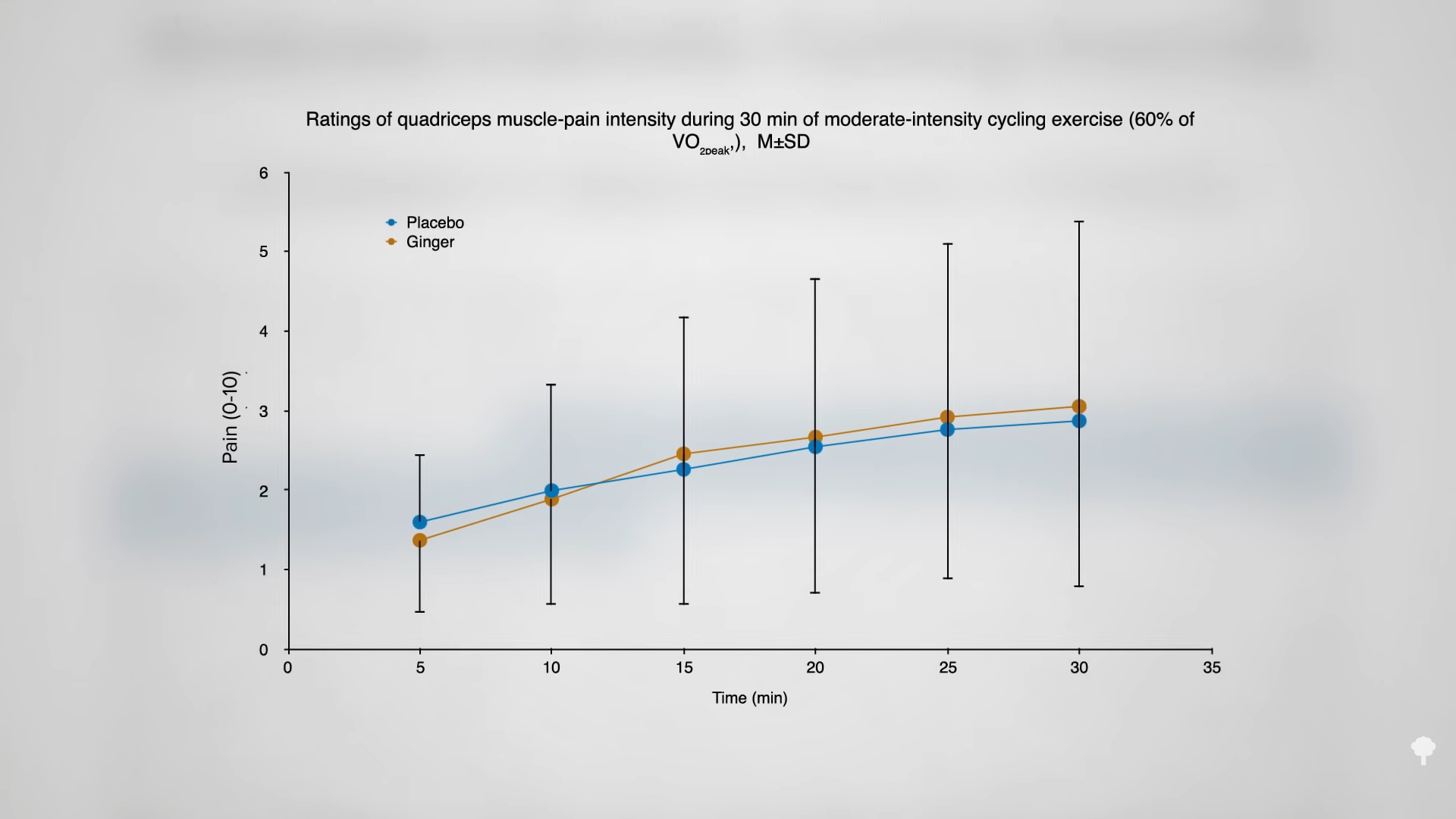

Okay, but does ginger work for muscle pain? Not acutely, apparently. You can’t just take it like a drug. When folks were given a teaspoon of ginger before a bout of cycling, there was no difference in leg muscle pain over the 30 minutes, as you can see below and at 3:34 in my video. “However, ginger may attenuate the day-to-day progression of muscle pain.” Taking ginger five days in a row appears to “accelerate the recovery of maximal strength following a high-load…[weight-lifting] exercise protocol.” When you put all the studies together, it seems “a single dose of ginger has little-to-no discernable effects on muscle pain,” but if you take a teaspoon or two for a couple days or weeks, perhaps in a pumpkin smoothie or something, you may be able to reduce muscle pain and soreness, and “accelerate recovery of muscular strength…”

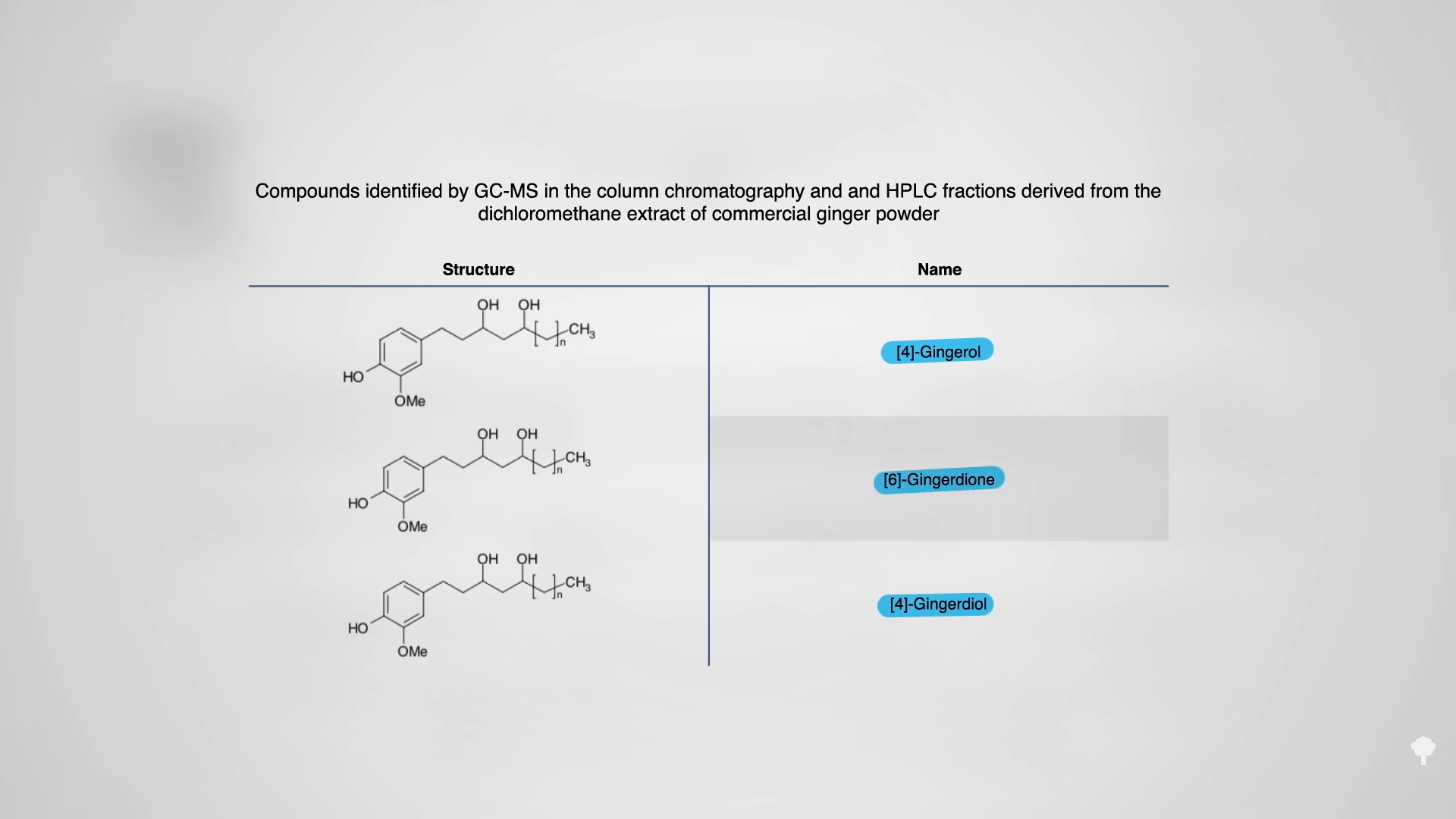

Is fresh ginger preferable to powdered? Maybe not. As you can see below and at 4:12 in my video, there are all sorts of compounds in ginger with creative names as gingerols, gingerdiols, and gingerdiones, but the most potent anti-inflammatory component may be compound called shogaols.

Interestingly, dried ginger contains more than fresh, which “justifies the uses of dry ginger in traditional systems of medicine for the treatment of various illnesses due to oxidative stress and inflammation.” In that case, why not just give the extracted shogaol component in a pill by itself? As you can see below and at 4:41 in my video, each of the active ginger components individually reduce inflammation, some more than others, but the whole ginger is greater than the sum of its parts.

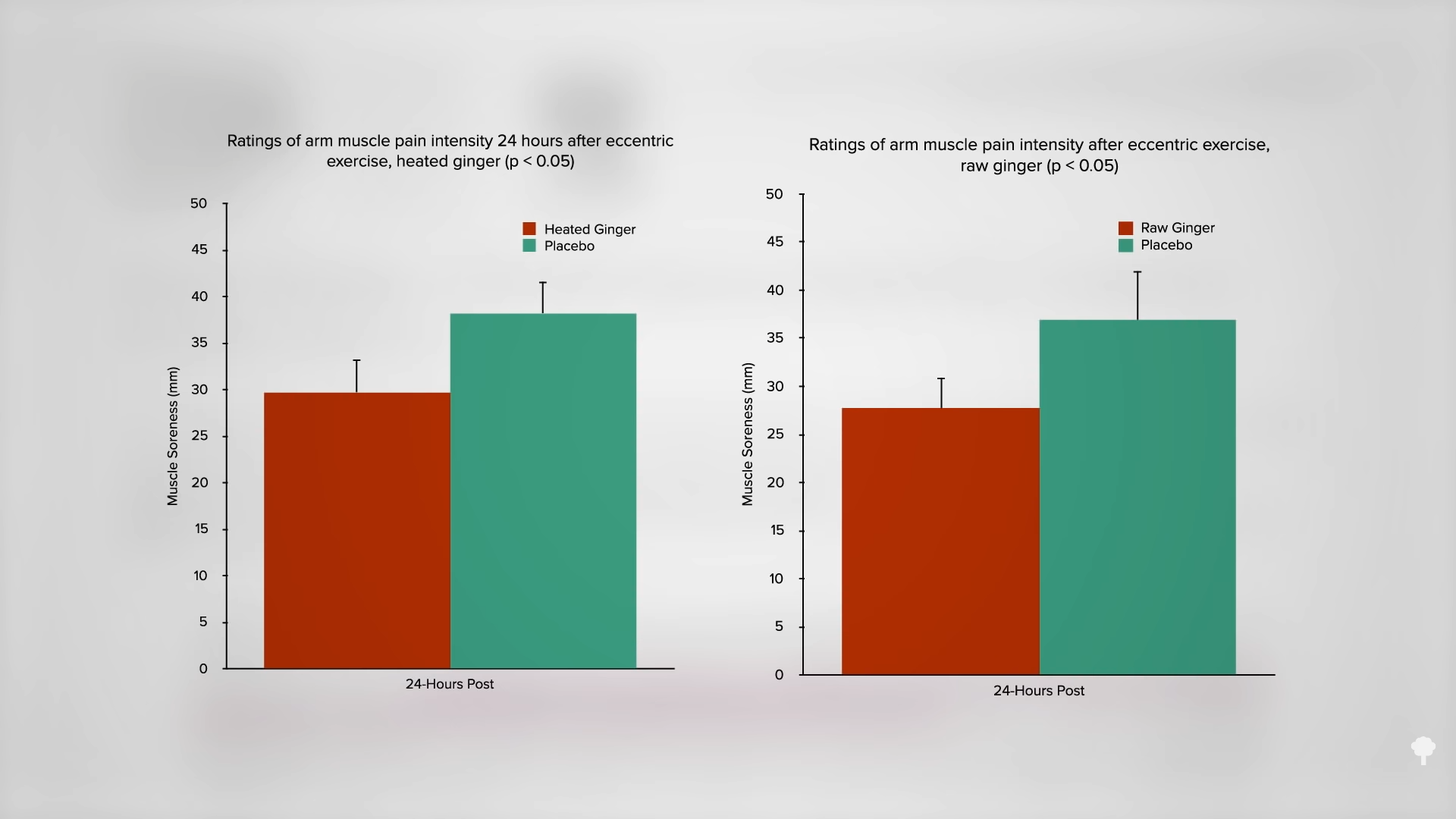

However, you can boost shogaol content of whole ginger by drying it, as they are the major gingerol dehydration products. Indeed, they’re created when ginger is dried. Heating ginger may increase shogaol concentration even more, so could heated ginger work better against pain than raw? You don’t know, until you put it to the test. A study examined the effects on muscle pain of 11 days of a teaspoon of raw ginger versus ginger that had been boiled for three hours. As you can see below and at 5:22 in my video, there was a significant reduction in muscle soreness a day after pumping iron in the cooked ginger group—and the same benefit was achieved with the raw ginger. Either way, “daily consumption of raw and heat-treated ginger resulted in moderate-to-large reductions in muscle pain following exercise-induced muscle injury.”

Here’s the link to the video I mentioned: Flashback Friday: Foods to Improve Athletic Performance and Recovery.

Key Takeaways

- The vast majority of college athletes and high school football players may use ibuprofen and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) both to treat inflammation and, prophylactically, to prevent pain and inflammation. The latter has potential risks, including gastrointestinal (GI) pain and bleeding, as well as damage to the kidney and liver.

- In a study of thousands of marathoners, taking painkillers before racing resulted in five times the incidence of organ damage and GI cramping was the most common adverse effect. The analgesics didn’t even work.

- In contrast to aspirin or ibuprofen-type drugs, ginger, which has anti-nausea properties, may actually improve GI function.

- Ginger extracts (e.g., the powdered ginger spice readily available in grocery stores) have been found to be “clinically effective” pain-reducing agents with a better safety profile than NSAIDs. Best results have been achieved with 1.5 to 2.0 g a day (about a teaspoon of ground ginger).

- NSAIDs suppress both the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme, which triggers inflammation, as well as cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), which protects stomach and intestinal linings; inhibition of COX-1 has been linked with GI irritation. Ginger appears to have no negative effect on the “good” COX-1 enzyme but may dramatically reduce the pro-inflammatory COX-2 enzyme.

- Although ginger may not acutely improve muscle pain, taking a teaspoon or two for consecutive days or weeks may reduce muscle pain and soreness, as well as hasten recovery of muscular strength.

- Shogaols may be the most potent anti-inflammatory component in ginger, and dried ginger contains more than fresh, so powdered ginger may be preferred to fresh.

- Shogaols are created when ginger is dried, but heating ginger doesn’t seem to work more effectively against pain than raw ginger. Indeed, “daily consumption of raw and heat-treated ginger resulted in moderate-to-large reductions in muscle pain following exercise-induced muscle injury.”

To read the original article click here.